The Definition of Net Working Capital Explained

Let's cut through the jargon. When you hear the term Net Working Capital (NWC), just think of it as a quick check on a company's financial health. It's the difference between its short-term assets and its short-term debts, telling you if it can comfortably cover its bills over the next year.

What Is Net Working Capital in Simple Terms?

Think about your own finances for a second. You have cash in your checking account and maybe some money a friend owes you. Those are your "current assets." On the other side, you have bills coming up—rent, credit card payments, etc. Those are your "current liabilities."

The cash you'd have left over after paying all those immediate bills is your personal version of net working capital. It's your financial breathing room. A business operates on the exact same principle, just on a much larger scale. NWC measures a company's liquidity and shows if its day-to-day operations are running smoothly.

The Basic Formula for NWC

At its core, the calculation is incredibly simple. You just pull two numbers from the balance sheet.

Net Working Capital = Current Assets - Current Liabilities

If the number is positive, the company has more than enough liquid resources to handle its short-term debts. If it's negative, it could signal a potential cash crunch down the road. But as we'll get into later, a negative NWC isn't always a red flag.

Breaking Down the Components

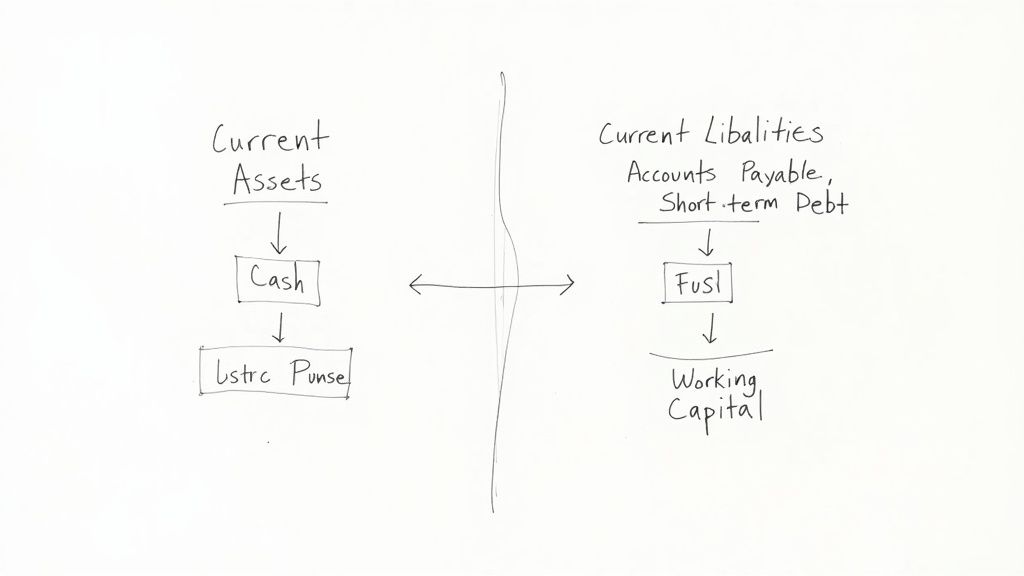

To really get what NWC is telling you, you need to understand what goes into each side of the equation. We're only looking at resources and obligations that are expected to be converted to cash or paid off within one year.

Current Assets: These are the assets a business relies on for its daily operations—the fuel in the tank. This bucket typically includes things like cash, inventory that's ready to be sold, and accounts receivable (money customers owe for products they've already received).

Current Liabilities: These are the company's bills due in the next 12 months. Think of things like accounts payable (money owed to suppliers), upcoming debt payments, and accrued expenses like payroll.

This simple subtraction gives you a powerful snapshot of a company's operational efficiency. It's a foundational concept in any finance or accounting interview because it reveals if a business can fund its daily grind without having to borrow money or sell off long-term assets just to keep the lights on.

Key Components of Net Working Capital at a Glance

To make this crystal clear, here’s a quick breakdown of what you'll typically find in each category when you're digging through a company's balance sheet.

Component Type | What It Represents | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

Current Assets | Resources expected to be converted into cash within one year. | Cash & Cash Equivalents, Accounts Receivable, Inventory, Marketable Securities, Prepaid Expenses |

Current Liabilities | Obligations due to be paid within one year. | Accounts Payable, Accrued Expenses (e.g., salaries), Short-Term Debt, Deferred Revenue |

Remember, the goal of this calculation is to isolate the assets and liabilities directly tied to the company's core, day-to-day business cycle.

Calculating Net Working Capital Step by Step

Alright, let's move from theory to practice. Figuring out a company's net working capital is actually pretty straightforward once you know your way around a balance sheet. The formula is dead simple, but the real skill is in knowing exactly which accounts to grab.

It really just boils down to three quick steps. Follow these, and you'll be able to nail the NWC for any company you're looking at.

Step 1: Pinpoint and Sum Current Assets

First things first, you need to find the "Current Assets" section on the balance sheet. This part of the statement tells you everything the company owns that it expects to turn into cash within a year.

You’re looking for a few specific line items. The usual suspects include:

Cash and Cash Equivalents: The most liquid asset there is.

Accounts Receivable (AR): This is the money customers owe the company for products or services they've already received.

Inventory: The value of all the stuff the company has on hand to sell—raw materials, works-in-progress, and finished goods.

Prepaid Expenses: Think of this as paying for things in advance, like next year's insurance premium or rent.

Add these up to get your Total Current Assets. This number gives you a good sense of the company's short-term operational firepower. (If you need a refresher on where this all fits, check out our guide on how to walk through the 3 financial statements).

Step 2: Identify and Total Current Liabilities

Next, slide your eyes down to the "Current Liabilities" section of that same balance sheet. These are all the bills and obligations the company has to pay off within the next 12 months.

Just like with assets, you’ll be adding up a few key accounts:

Accounts Payable (AP): This is the flip side of AR—it’s the money the company owes its own suppliers.

Accrued Expenses: Expenses the company has racked up but hasn't paid for yet, like employee salaries or taxes that are due soon.

Short-Term Debt: Any loans or debt payments that have to be settled within the year.

Deferred Revenue: This is cash a customer paid upfront for something the company hasn't delivered yet.

Summing these gives you Total Current Liabilities. This is the total cash the company is on the hook for in the near term.

Step 3: Apply the Net Working Capital Formula

Got both your totals? Great. The last step is just simple subtraction. The classic definition of net working capital is simply the difference between what a company owns (short-term) and what it owes (short-term).

NWC = Current Assets − Current Liabilities

This basic formula is a cornerstone of financial analysis. It's the quickest way to get a read on a company's liquidity and operational health. Anyone in finance uses this constantly to see if a business can cover its immediate bills.

Let's make this real with an example. Imagine a small company, "RetailCo," with these numbers pulled from its balance sheet:

Example Calculation for "RetailCo"

Balance Sheet Item | Amount | Category |

|---|---|---|

Cash | $50,000 | Current Asset |

Accounts Receivable | $75,000 | Current Asset |

Inventory | $100,000 | Current Asset |

Accounts Payable | $60,000 | Current Liability |

Short-Term Loan | $40,000 | Current Liability |

Accrued Salaries | $15,000 | Current Liability |

First, let's tally up the Total Current Assets: $50,000 (Cash) + $75,000 (AR) + $100,000 (Inventory) = $225,000

Next, we'll do the same for Total Current Liabilities: $60,000 (AP) + $40,000 (Loan) + $15,000 (Salaries) = $115,000

Finally, we apply the formula: $225,000 (Current Assets) - $115,000 (Current Liabilities) = $110,000 (Net Working Capital)

So, RetailCo has a positive NWC of $110,000. This tells us it has a healthy buffer to meet its short-term financial obligations. They aren't at risk of running out of cash anytime soon.

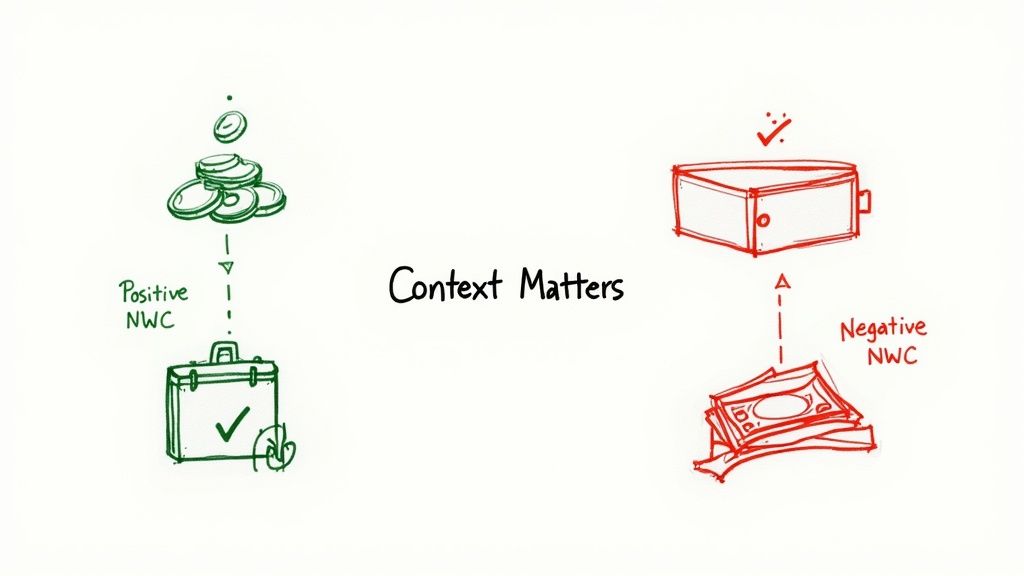

What a Positive or Negative NWC Really Means

Once you run the numbers, you're left with a single figure for Net Working Capital. But don't be fooled by its simplicity. That number tells a crucial story about a company's operational pulse and its day-to-day financial health. Interpreting NWC is less about the number itself and more about understanding the business model humming away behind it.

At first glance, it seems straightforward. Positive NWC suggests a company has more than enough liquid assets to cover all its bills due in the next year. Negative NWC, on the other hand, looks like a red flag, signaling potential cash flow problems on the horizon.

But this is where a surface-level definition of net working capital can get you into trouble. Context is everything. What looks like a warning sign for one company might be a hallmark of incredible efficiency for another.

The Story of Positive Net Working Capital

Generally, positive NWC is a good thing. It means a company has a buffer. It can comfortably pay its suppliers, cover payroll, and handle short-term debts without having to scramble for cash or sell off long-term assets.

Think about a classic manufacturing company. It needs to buy raw materials and pay factory workers long before it gets paid by its customers. A healthy positive NWC ensures it has the cash on hand to manage this gap, keeping the production line moving smoothly.

However, a huge NWC isn't always a good sign. It could actually be a red flag pointing to inefficiency. It might mean:

Inventory is piling up: The company isn't selling its products fast enough, tying up precious cash in unsold goods sitting in a warehouse.

Receivables are too high: The business is struggling to collect cash from its customers on time.

Idle cash: Too much cash is just sitting in the bank instead of being invested back into the business to fuel growth.

The goal is balance. A company needs enough NWC to operate without stress, but not so much that it suggests sloppy asset management.

When Negative Net Working Capital Is Actually a Good Thing

Now for the counterintuitive part. While negative NWC can spell disaster for many businesses, for some, it's a sign of a highly efficient, cash-generating machine.

This usually happens in businesses with a lightning-fast cash conversion cycle. These are companies that collect cash from customers almost immediately but get to pay their own suppliers on much longer timelines.

The classic example is a fast-food chain like McDonald's or a grocery store. You pay for your burger or your groceries right now, instantly boosting the company's cash. But that company might have 30, 60, or even 90 days to pay its suppliers for the buns, beef, and produce.

This brilliant business model allows the company to use its suppliers' money as a form of free, short-term financing. It's collecting cash from thousands of customers long before its own bills come due. For instance, a retailer like Walmart has historically used this model to fund its operations and expansion, all while maintaining negative working capital.

The Key Takeaway: A negative NWC isn't automatically bad. It forces you to ask why it's negative. Is it because the business is struggling to pay its bills? Or is it because the business model is so efficient that customers pay it long before it has to pay anyone else?

To help you quickly size up these different situations, here’s a table breaking down what each NWC scenario might indicate.

Interpreting Different NWC Scenarios

NWC Scenario | General Interpretation | Potential Sign of Strength | Potential Sign of Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

High Positive | The company has a strong liquidity buffer. | Sufficient cash to fund operations and withstand shocks. | Inefficient use of assets; cash tied up in slow-moving inventory or uncollected receivables. |

Low Positive | The company can meet its obligations but has a thin buffer. | Lean and efficient operations with minimal idle cash. | At risk of a cash crunch if unexpected expenses arise or sales slow down. |

Negative | Current liabilities exceed current assets. | Highly efficient cash conversion cycle (e.g., retail, restaurants). | Inability to pay short-term bills; potential cash flow crisis looming. |

Ultimately, interpreting the definition of net working capital correctly requires you to think like an analyst, not just a calculator. The number is just the starting point. The real insight comes from digging into the industry norms, the company's business cycle, and the story the balance sheet is trying to tell you.

How NWC Is Adjusted for Business Valuation

When you're valuing a company for an acquisition, a simple snapshot of net working capital from one balance sheet just won't cut it. The stakes are too high. In a deal setting, analysts go way beyond the basic formula to figure out the true, sustainable amount of capital needed to run the business day-to-day.

This isn't just an academic exercise—it directly impacts the final purchase price. A buyer needs to know exactly how much gas will be in the tank on day one. If the NWC is too low, they’ll have to immediately inject their own cash just to pay suppliers and keep the lights on. Nobody wants that kind of surprise.

Why Normalization Is a Non-Negotiable Step

Imagine trying to value a retailer using only its December balance sheet. The numbers would be totally warped by the holiday rush—sky-high inventory and receivables. That’s not a realistic picture of the business for the other eleven months of the year. A single snapshot can be incredibly misleading due to seasonality, big one-off orders, or even a seller trying to make their numbers look good right before a sale.

To get around this, analysts calculate a normalized Net Working Capital. This isn't just one data point. It’s an average, usually taken over 12 to 24 months, to smooth out the bumps.

By averaging NWC across a full business cycle, you can filter out the noise from seasonal peaks, bulk purchases, or weird payment terms. What you’re left with is a baseline NWC that reflects the company’s real, ongoing operational needs.

This normalized figure becomes the "NWC target" in a deal. It’s often one of the most heavily negotiated parts of a purchase agreement because it sets the standard for what the buyer expects to inherit at closing.

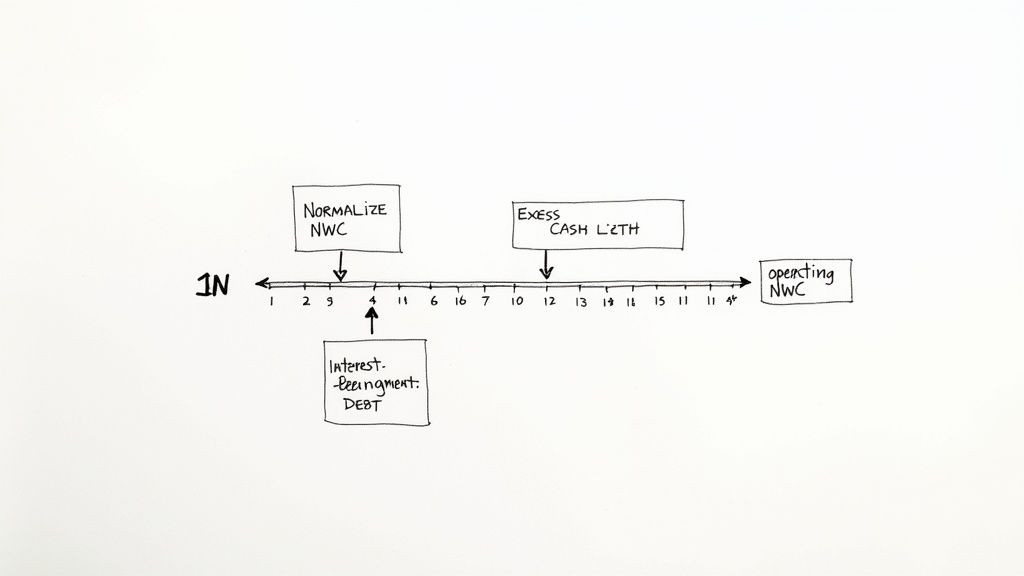

Isolating True Operating NWC

On top of normalization, another key step is to strip out anything that isn't core to the business's daily operations. A textbook NWC calculation includes all current assets and liabilities, but for valuation, we only care about the items tied directly to generating revenue.

The goal is to calculate Operating Net Working Capital (ONWC). This usually means making a few key adjustments:

Removing Excess Cash: A business needs some cash for things like payroll, but anything above that minimum operating level is considered non-operational. Sellers typically "sweep" this excess cash at closing, so it’s backed out of the calculation.

Excluding Interest-Bearing Debt: Short-term loans or lines of credit are financing decisions, not operating ones. They show how a company funds itself, not how well it manages its sales and inventory cycle. These get removed, too.

This refined formula—(Current Operating Assets) - (Current Operating Liabilities)—gives you a much cleaner look at the capital locked up in the company's core business. To see how these adjustments work in the real world, it's helpful to review a few investment banking case studies where these details can make or break a deal.

The Critical Link Between NWC and Cash Flow

Why all the fuss? Because changes in net working capital have a direct impact on a company's free cash flow (FCF), which is the foundation of nearly every valuation model.

When NWC increases, it means more cash is being tied up in the business (like building up inventory or waiting longer for customers to pay). This is a use of cash, so it reduces free cash flow.

On the flip side, when NWC decreases, it means the company is running more efficiently and freeing up cash. This is a source of cash, so it increases free cash flow.

This is exactly why M&A agreements hammer out target NWC levels based on historical averages. The final NWC figure is a sophisticated tool used to ensure fairness, protect a buyer from a day-one cash crunch, and value a business based on its true, sustainable performance.

Mastering NWC for Finance Interviews

Knowing the technical definition of Net Working Capital is just the entry ticket. To really stand out in a high-stakes finance interview, you have to go beyond the formula and show you understand what it means for the business.

Interviewers aren't just looking for a human calculator. They want to see if you can connect the numbers on a balance sheet to the real-world operations of a company. This is your playbook for turning a basic technical question into a response that actually impresses.

Answering "Why Is NWC Important?"

One of the first questions you'll likely get is, "Why do we care about Net Working Capital?" A weak answer just spits back the formula. A great answer explains why it’s a critical vital sign for a company's operational health.

Your response should hit on a few key ideas:

Liquidity Management: NWC is the go-to metric for figuring out if a company can cover its short-term bills. It tells you if they have enough cash from operations to keep the lights on without scrambling for emergency funding.

Operational Efficiency: It’s a report card for management. High NWC might sound good, but it often means cash is needlessly tied up in dusty, slow-moving inventory or that customers aren't paying their bills on time.

Cash Flow Prediction: Changes in NWC are a direct plug into a company's free cash flow calculation. You can't build a reliable valuation model without understanding what drives it.

A sharp, confident response might sound something like this:

"NWC is critical because it's a direct measure of a company's operational liquidity and efficiency. Beyond just seeing if a company can pay its bills, it tells us how well management is converting operational assets like inventory and receivables into cash. This is crucial for valuation, as changes in NWC directly impact a company's free cash flow."

Common NWC Interview Questions and How to Answer Them

Once you've laid the groundwork, interviewers love to poke holes in your understanding with follow-up questions. They want to see if you can apply the concept, not just define it. Here are a couple of classics and how to handle them.

Question 1: "How do changes in NWC affect cash flow?"

This is fundamental. Don't just say, "an increase in NWC decreases cash flow." Explain the why.

An increase in Net Working Capital is a use of cash. For example, if a company's accounts receivable grows, it means they've recorded revenue but haven't actually collected the cash yet. Similarly, if inventory piles up, they've spent real cash to produce goods that are just sitting on a shelf. Both scenarios tie up cash that could be used elsewhere, which is why it reduces the company's free cash flow.

Question 2: "Can a company have negative NWC and still be healthy?"

This is a classic curveball to see if you can think beyond the textbook. The answer is a confident "yes," but you have to back it up with the right examples.

Explain the Model: Talk about businesses with killer cash conversion cycles. Think grocery stores (like Kroger), fast-food chains (like McDonald's), or massive e-commerce retailers (like Amazon).

Provide the Logic: These companies get cash from customers instantly at the register or online checkout. But they pay their suppliers on terms—often 30, 60, or even 90 days later. This lets them use their suppliers' money to fund their daily operations, which is a sign of incredible efficiency, not weakness.

Avoiding Common Interview Pitfalls

Plenty of candidates stumble on NWC questions. It's usually not because they forget the formula, but because they miss the business context. Here are the traps you need to avoid.

Sticking to the Formula: Never just say "Current Assets minus Current Liabilities." Always connect that calculation back to what it represents: a company's operational health and liquidity.

Ignoring Industry Context: What's considered a "good" NWC level is completely different depending on the industry. A capital-intensive manufacturer is going to look nothing like a lean software company. Always add that nuance.

Confusing NWC and Operating NWC: When you're talking about valuation, be specific. Mention that you'd adjust for non-operating items like excess cash and short-term debt to get a cleaner, more accurate picture of the business's core capital needs.

For a deeper look at how technicals are tested, our guide on the four types of technicals you will get asked in your investment banking interview will give you a serious edge. Nailing these details shows you're not just prepared—you're thinking on another level.

Common NWC Questions (And How to Answer Them)

Even after you’ve got the formulas down, a few tricky questions about Net Working Capital always pop up. This is where interviewers separate the candidates who memorized a definition from those who actually get it.

Let's walk through the most common points of confusion to make sure you're ready for them.

What’s the Difference Between Working Capital and Net Working Capital?

This is a classic "gotcha" question. While people use these terms interchangeably in casual conversation, in finance, precision matters.

Working Capital is just your total current assets. Think of it as the gross amount of resources you have on hand to run the business day-to-day—all your cash, inventory, and receivables combined.

Net Working Capital is what’s left after you subtract current liabilities from current assets. This number gives you a much better sense of a company’s actual liquidity and ability to cover its short-term bills.

Here’s a simple analogy: "Working Capital" is your total monthly paycheck. "Net Working Capital" is what you have left after you've set aside money for this month's rent, utilities, and credit card bill. The net figure tells you how much financial breathing room you really have.

Why Is Cash Excluded From NWC in Valuations?

This is a crucial point that separates a textbook answer from a professional one. When you're building a financial model for an M&A deal or a valuation, you’re trying to understand the capital required to run the company's core operations.

To do that, analysts calculate what’s often called "Operating NWC."

This adjusted formula intentionally pulls out items that aren't tied to the daily grind of the business. Excess cash gets excluded because it’s a non-operating asset—it’s not actively being used to produce and sell goods like inventory is. Likewise, short-term debt is removed because it’s a financing decision, not an operational one.

By stripping out these non-operational items, you get a cleaner, apples-to-apples view of a company's efficiency. This adjusted definition of net working capital is the standard for any serious financial modeling.

How Can a Company Improve Its Net Working Capital?

Improving NWC is all about tightening up the cash conversion cycle—that's the time it takes for a dollar invested in inventory to make its way back into the company’s bank account as cash.

There are three main levers a company can pull:

Get Paid Faster (Accelerate Accounts Receivable): The quicker a company collects from customers, the better. This can mean offering discounts for early payment or having stricter credit terms.

Hold Less Stuff (Optimize Inventory): Every unsold product sitting in a warehouse is cash that isn't working. Smart inventory management, like a just-in-time system, keeps capital from collecting dust.

Pay Slower (Extend Accounts Payable): If you can negotiate longer payment terms with your suppliers, you’re essentially using their capital as a short-term, interest-free loan. This keeps your cash in your account for longer.

Each of these moves frees up cash, improves liquidity, and means the company doesn't have to borrow as much money to fund its daily operations.

Is a High Net Working Capital Always a Good Thing?

Not at all. While you definitely want a healthy positive NWC, an excessively high number can be a red flag for inefficiency. Think of it as an opportunity cost.

A bloated NWC could mean:

Too much cash is trapped in slow-moving or obsolete inventory.

The company is doing a poor job collecting money from its customers on time.

Capital is sitting idle instead of being invested in growth projects, R&D, or paying down high-interest debt.

The sweet spot is a strategic balance: having enough liquidity to run operations smoothly without letting capital go to waste. Like most things in finance, the "right" number depends entirely on the company and its industry.

Ready to move beyond definitions and start mastering the real-world application of finance concepts? AskStanley AI is the ultimate training partner for aspiring investment bankers. With infinite technical questions, realistic mock interviews, and adaptive drills, you can build the confidence and precision needed to ace your interviews. Stop guessing what to study and start getting offer-winning answers. Accelerate your interview prep with AskStanley today!